Owned and operated by Joseph Wagner in Napa Valley, Copper Cane Wines & Spirits houses a collection of brands that are crafted to offer a touch of luxury for everyday indulgence. The wine portfolio includes a list of six unique wine brands: Belle Glos, Elouan, Quilt, Böen, Threadcount, and Steorra.

Go With Your Palate

Go With Your Palate - Behind the Name

Go With Your Palate - Joe Wagner

Go With Your Palate - Oregon Thumbprint

Go With Your Palate - Taste of Elouan

Go With Your Palate - Farming a Sense of Place

Go With Your Palate - The Patchwork of Napa Valley

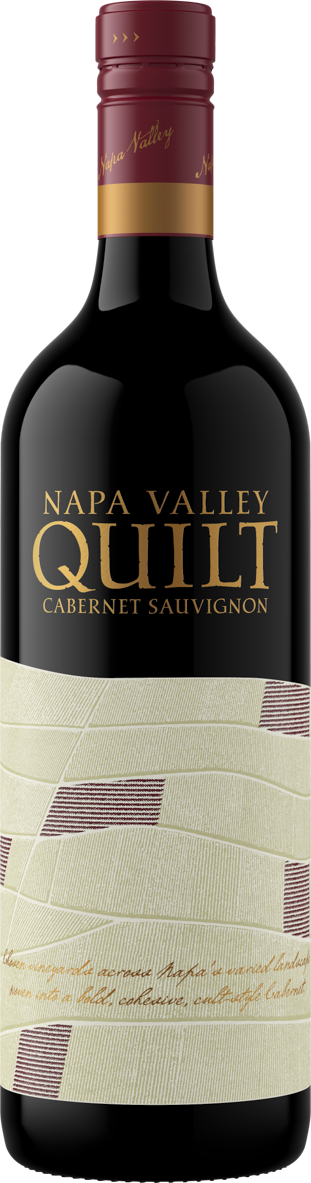

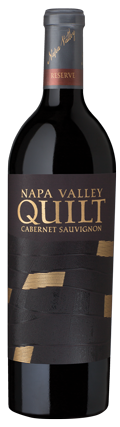

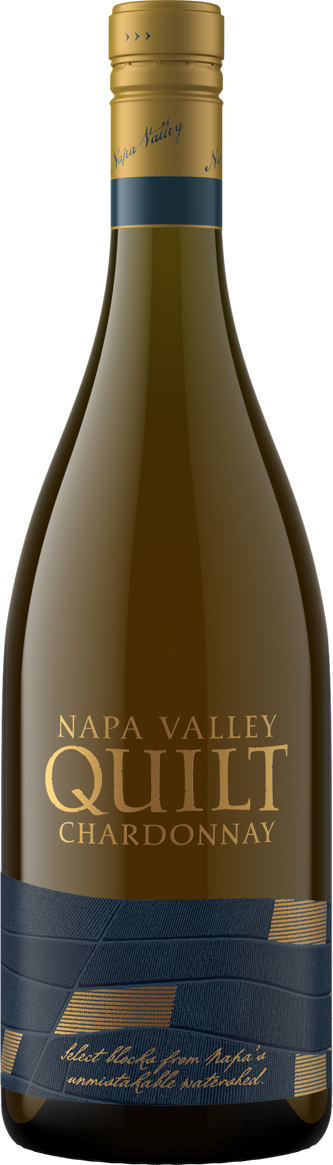

Drawing from a patchwork of six prime Napa Valley AVAs to create full-bodied, rich, and decadent wines, Quilt exemplifies the classic structure of wines from the region, while the blending of fruit from a variety of vineyards allows the wines to maintain more complexity and a better style consistency from vintage to vintage.

Quilt

Cabernet Sauvignon

Quilt

Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve

Quilt

Chardonnay

Quilt

Red Wine

Owner/ winemaker, Joe Wagner chose the name Belle Glos to honor his grandmother, Lorna Belle Glos Wagner. Joe’s goal for each of the Belle Glos single-vineyard Pinot Noirs – Dairyman, Las Alturas and Clark & Telephone – is to express the uniqueness of each vineyard site, and to craft genuine wines that are complex, fruit-forward and rich.

Belle Glos

Las Alturas Pinot Noir

Belle Glos

Clark & Telephone Pinot Noir

Belle Glos

Dairyman Pinot Noir

Belle Glos

Balade Pinot Noir

Belle Glos

Eulenloch Pinot Noir

Belle Glos

Oeil de Perdrix Pinot Noir Blanc

A translation of ‘The Farm’, Böen is a reflection of Joe Wagner’s agricultural roots as a lifelong grape grower and winemaker. Böen exemplifies the ideal flavors and structure of Pinot Noir from the Russian River Valley, an area renowned for its cool, foggy air and lengthy growing season that allows for fully developed flavors and natural acidity.

BÖEN

Russian River Valley Pinot Noir

BÖEN

Santa Lucia Highlands Pinot Noir

BÖEN

Santa Maria Valley Pinot Noir

BÖEN

Sonoma County, Monterey County, Santa Barbara County Pinot Noir

BÖEN

Sonoma County, Monterey County, Santa Barbara County Chardonnay

Elouan is the result of California winemaker, Joe Wagner venturing up to Oregon, one of the world’s renowned grape growing regions. The goal: to produce Pinot Noir and Chardonnay with depth of flavor, vibrancy and suppleness. For this wine we brought together fruit from three distinct terrains along Oregon’s premiere Western vineyards which harmonize beautifully when blended as one.

Elouan

Pinot Noir

Elouan

Rosé

Elouan

Chardonnay

Elouan

Klamath’s Kettle Reserve

Elouan

Missoulan Wash Reserve

A lover of champagne, Joe Wagner has long wanted to create a classic sparkling wine using Pinot Noir and Chardonnay fruit. Steorra, his first-ever sparkling wine, takes its name from the Old English word for ‘star’ and is a non-vintage Brut style sparkling sourced from the cool-climate Russian River Valley, esteemed for these grape varieties.

Steorra

Russian River Valley Brut Sparkling Wine

Beran, meaning “The Bear” is forever a figure of strength and head-strong drive. With the same power and conviction our Zinfandels are grown and crafted without compromise. Zinfandels that embody the spirit of California. We source extraordinary fruit from heritage old-vine plantings and and up-and-coming vineyards from within Sonoma County, Napa Valley and other notable regions to make Zinfandel that is worthy of its rich history in the state.

Beran

California Zinfandel

Beran

Sonoma County Zinfandel

Beran

Napa Valley Zinfandel

Named for the 1841 upper Napa Valley land grant, “Rancho Carne Humana”, the bold and nuanced character of these wines is a worthy expression of the rich history and diverse soils of the land from where the fruit is grown. We select “field blends” to be co-fermented as single lots to create opulent, richly textured wines with greater depth and integration.

Carne Humana

Napa Valley Red Wine

Carne Humana

Napa Valley White Wine

Currently featured in

Cabernet Sauvignon

A patchwork of prime Napa Valley vineyards are sourced to create this classic Cabernet Sauvignon made in the style my family has always loved. Enjoy this seamless balance of flavors and always go with your palate.

Follow Our Brands

@coppercanewinesLooking for Trade Tools?

Click the button below for all your sales and marketing needs such as tasting notes, bottle shots, logos and shelf talkers.